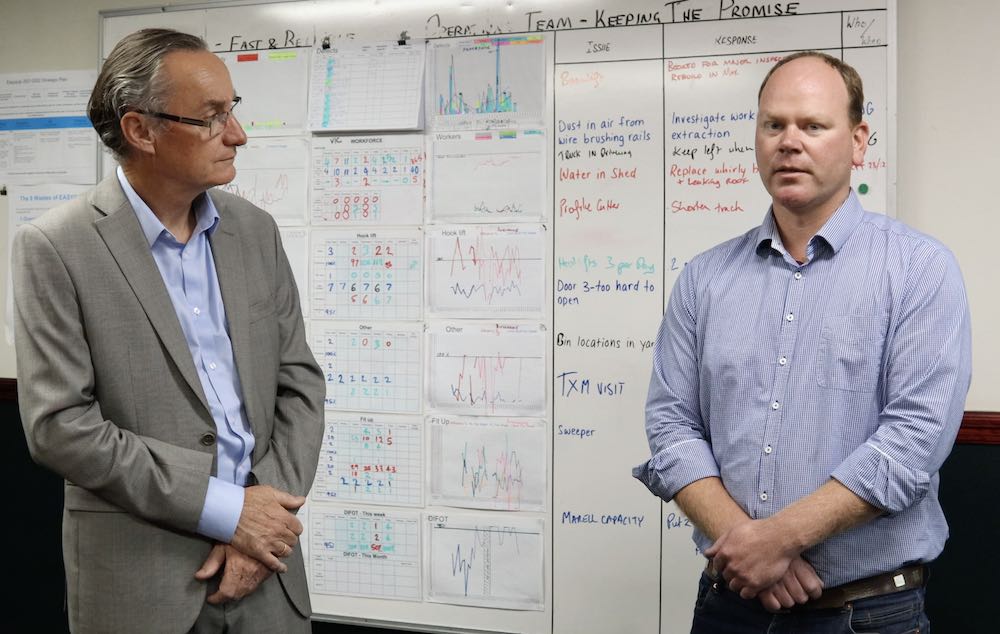

Back in 2000-2002 I managed a packaging business for two years before a restructuring led me to volunteer for a retrenchment package. I was disappointed at the time, because it is had been a great job and I really thought two years was not long enough to make a sustained difference. However, I subsequently discovered that my two years made me the longest-serving General Manager of that business. Over the last 20 years that business has had at least 15 leaders.

This may sound like an extreme example, but it is not. I regularly come across businesses who have changed their key line managers every one to two years. It seems that in some businesses, being the General Manager or Operations Manager is a high risk occupation! In an earlier blog I talked about how companies can not recruit their way to success. However, I think the problem of turnover of senior line managers needs particular attention.

Why Senior Line Leaders Fail

I think the most important point to make here is that they usually don’t fail! They more often don’t get given the opportunity to succeed. Here’s the typical pattern:

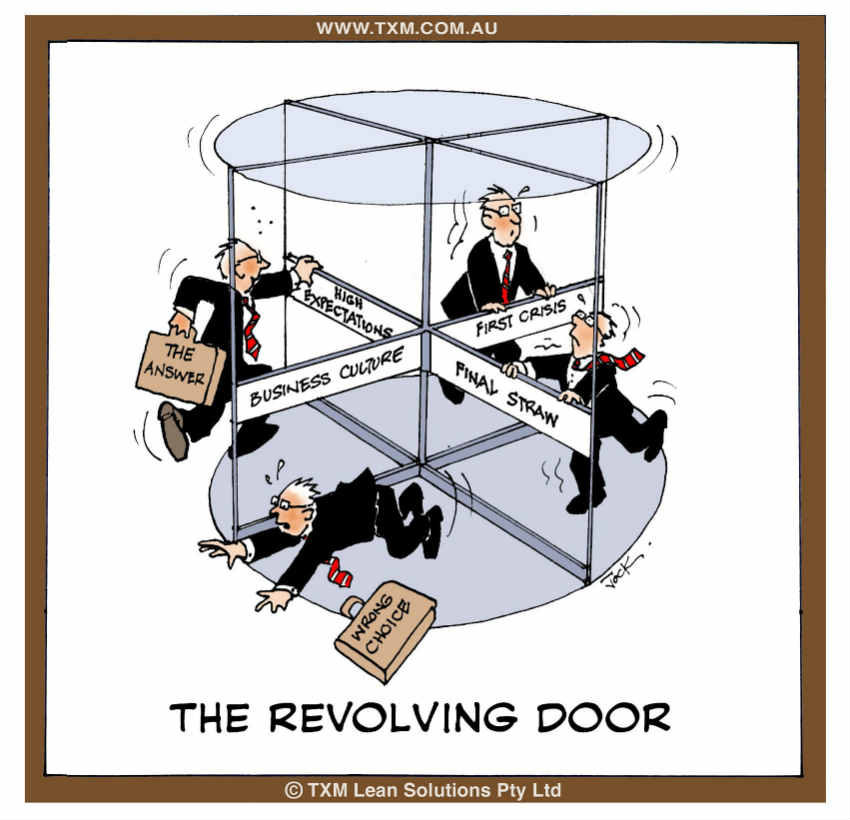

A new manager is hired. On day one they are regarded as the answer to all the business’ problems. Expectations are sky-high and everyone feels positive, especially the directors. This lasts for a few months until the business encounters its first crisis. It might be a quality issue, not meeting deliveries on time, the loss of a customer or a disgruntled employee. The directors of the business are shocked at the crisis. Surely once they hired the new manager, these problems would stop? They start to worry that the new manager is not a “superhero” after all. They visit the business and talk to some long-term key staff. They don’t like what they hear. There are lots of angst-ridden discussions among the directors. “Have we got the wrong guy?”, they ask themselves. They usually don’t discuss their concerns directly with the manager involved in case honest feedback causes the manager to “lose motivation”. They then decide that they need to get more involved in the business again. They start regularly walking the floor, attending meetings and talking to those long-term employees that they trust. The staff are relieved to see the directors back involved in the business and share their concerns. The directors try their best to stay “hands-off” and let the new manager do their job, but the directors’ very presence in the business sends a clear message about their lack of confidence in the new manager. The new manager attempts to continue to manage, but their authority is now critically undermined. Staff may (or may not) have goodwill towards them, but the directors own the business, don’t they? Staff are canny enough to know that the directors will be around long after the new manager is gone. Management team meetings become a façade as all the staff knows that the manager is on borrowed time (they have seen this movie before). Inevitably more crises occur because staff are reluctant to follow the manager’s directions, but the directors are still trying to be “hands off”. As a result, there is no direction and the staff become passive and don’t take any action when they see problems arising. The directors get further and further involved, the authority of the manager is totally undermined and eventually, the manager is fired or resigns. The directors then recognise that they made the wrong choice of manager and go back to the recruitment market and “try and get it right this time”.

If this sounds like your business, then read on!

So What Went Wrong?

I see companies play this “movie” over and over again, hiring and firing manager after manager. In the meantime, their business goes backward, good staff leave and complacency, poor culture and resistance to change becomes entrenched. So why does this happen?

There is a quote we like to use that is attributed to a senior manager at Toyota:

“We get brilliant results from average people operating and improving brilliant processes. Our competitors get mediocre results from brilliant people working around broken processes. Then, when they fail, they hire even more brilliant people.”

This really sums up the problem. If your underlying business processes and culture are broken, no matter how good the person is that you hire, they will inevitably fail. The fact is the business crises that you expect your new manager to address will inevitably continue. They are just built into the DNA of your company. Of course, you may get a short term reprieve with a new manager, this can be just random variation (crises don’t occur every day) or can be the “halo” effect because everyone is just a bit more on their toes because of the new manager. Inevitably though, unless your underlying processes and culture are addressed, you will have another crisis and/or performance will fall back to its long term trend.

Culture is Not Easy to Change

Often the root cause of the problems in your business is tied up in the culture of your business. These are the unwritten assumptions, values and expectations that guide everyone’s behaviour. These cultural norms have often been established by the directors and founders of the business over many years. They are maintained by your long term loyal staff and are not readily changed by a new manager. There are many examples of counterproductive cultural practices. Some we have seen include a cavalier approach to safety, a willingness to accept near enough is good enough on quality or preparedness to promise the customer anything they want, regardless of whether it can be delivered. A common one is a culture of short cuts, where a failure to follow the correct process is accepted or even commended if it “gets the job done”. This may be seen as “bureaucracy busting” and “being responsive” in a small company, but can be disastrous as your company becomes larger and less skilled staff adopt the culture of taking short cuts.

The new manager will not be able to change the culture of your business on their own. The directors will need to help them with this. They will most likely see the cultural issues as soon as they start and therefore the directors need to invite challenging feedback about the cultural issues that need to be addressed. The directors then need to support them by consistently sending the message to staff that the old ways will no longer be acceptable – and demonstrate this in their own behaviour.

It is Not Just About Results

Naturally, when you employ a new senior manager, you will want to see improvement in financial performance. However, if you want long term change, you need to address how you are achieving those results. This means your business process. Therefore, as well as measuring your manager on financial metrics, you also need to measure them on how they are improving the way you do business. These things may not lead to immediate bottom-line results, but this does not mean they are unimportant. Typical processes that might need addressing include your core order fulfilment process, manufacturing processes, warehouse processes, quoting process, new product development/introduction process, HR processes, and financial processes.

Standard ways of working are key to defining the new baseline standard for all people to follow. Value stream maps can be incredibly useful in understanding the root causes of your process problems and developing solutions. They allow you to move past the “tribal knowledge” controlled by the long term staff and start making decisions and designing processes based on facts. Encouraging the new person to confront the standard work and to expect that all staff perform standard duties is the key to breaking this cycle. The challenge is the directors need to change first.

It is likely that your new manager will need help to redesign your business processes, so be prepared to support them with investment in the advice, resources, and tools they need to make that change. Remember that the managers’ job is to lead the business, not to get down in the details of facilitating team workshops on process design or developing the capital budget for a new warehouse or production line.

The challenge as directors is that you may need to be prepared to support a manager who is not getting short term results and may even be facing a few crises if he is clearly taking the steps needed to address the cultural and process issues that might be causing the crises. On the other hand, you may need to correct a manager who is getting short term results but not addressing the underlying issues in your business.

What to Do When Things Go Wrong

All this stuff is easy for me to say, but as director of a medium-sized business myself, I know how hard it is to stand back and watch things going wrong. Therefore, you need a strategy to deal with the situation when things go wrong.

When the new manager starts, give them one to two months to learn the business and their role. Then they will need a plan. Share with them your strategic goals for the business and the overall outcomes you expect from their role. Then ask them to develop a plan of their own. Encourage them to work with their management team on this. Once this plan has been developed, be prepared to (respectfully) challenge and negotiate it. When the plan is agreed, then you need to schedule regular (ideally weekly or at least monthly) catch-ups to review the progress of the plan (not the current business results). This then gives you the means to track how the manager is working towards the longer-term goals in your business as well as responding to short term issues.

Often businesses employ a senior manager as part of a succession plan for the owners. In this case, I don’t think it works well when you, the owner or executive director, completely exits the business when the new manager is appointed. Unless you have plans to become a completely silent owner and maybe move overseas, you are going to want to have some ongoing involvement. Otherwise, if you disappear and reappear when there is a crisis, it will be seen as you losing confidence in the new manager. You need to define what your ongoing involvement will be and have a clear agreement with the new manager on this. You need to define when you will be in the business and what your role will be. You might want to have regular walkarounds, but it is better to do these with the new manager so staff see you aligned with them. When staff contact you directly with grievances, direct them back to their manager unless they are reporting something unethical or illegal. Don’t encourage “back channel” communications as this can be very destructive.

When something does go wrong, you need to ask “why” not “who”. Ask “What should have happened? And how did this situation arise?” Expect a thorough root cause analysis and corrective action plan incorporating both short term fixes to get things back on track as well as longer-term corrective actions to prevent it from happening again. You can then follow up the implementation of these corrective actions with a weekly review in the weeks following the crisis. Judge your manager on their ability to identify the root cause, develop credible corrective actions and then map out and follow a plan to implement those corrective actions, rather than on the crisis itself. Also take note of how they engage their immediate team in solving the problem and implementing the solution. If you are holding them accountable for implementing the overall plan, you should see them holding their team accountable for implementing the various elements of it.

Some Warning Signs

Recruitment always has a margin of error and so not every manager you hire will be a success. There are some warning signs that you need to be aware of that might reveal that you do have the wrong person and, at the very least should prompt some immediate discreet corrective action:

- Failing to develop a team around them. Is your manager building a high calibre team around them? Have they thought of their own succession? Are they giving their team challenging responsibilities or instead of doing their job for them? Don’t go and ask the team what they think of their new manager, as this will undermine the manager. However, do take careful note of how they are working with their team. Listen to their language – is it all about them and what they are doing or are they sharing the credit around and talking about how their team is developing? If you have concerns, then you may want your manager to share with you a plan specifically around how they are developing their own team.

- Refusing help. This is a depressingly common problem, where we see managers who seem to believe that they have to do everything themselves in order to somehow prove their value. You need to deal with this ego trip fairly quickly and indicate to them that they will not get more credit for their success if they “go it alone”, but their risk of failure will be much higher. My view these days is that directors probably need to be quite assertive upfront on this and make it clear to the new manager that you expect them to use the help and resources on offer even if they believe they can “do it themselves”. The ability to marshal internal and external resources to improve business outcomes is in fact a key skill of a successful manager.

- Bullying and Intimidation. Sadly, this is quite common and it does not necessarily come with verbal abuse and screaming. It can be just quietly delivered threats and inferences about subordinates’ job security. This often occurs as the new manager comes under pressure in a crisis. A State Department official once described John Bolton, George W. Bush’s Ambassador to the UN as a “kiss up, kick down kind of guy”. Sadly there are a lot of “kiss up, kick down” guys around. Finding them out is not always easy. Telltale signs can be apparently excessive effort at trying to impress you, blaming others (usually their team or peers) when things go wrong, taking credit for others’ work and belittling the contribution of others. They will also typically be reluctant to allow their team to have direct contact with you. Therefore, all communication will be through them.

- Passive acceptance. When things go wrong this kind of manager will wring their hands, be very empathic, but put things down to bad luck or fate. They will accept that things are as good as they will ever be and will blithely walk past situations that are clearly not right without comment. Often, they will blame external factors (the market, raw material prices, the union) for problems and will have no plan for how to manage these factors as they are “out of our control”.

If you see these warning signs, then the action you need to take is to give feedback. Set some clear goals with a defined time frame and follow up. Usually, I like to get managers to put together a 12-week turnaround plan and then schedule weekly reviews to track their progress. Remember, do this discretely and don’t go asking your manager’s subordinates what they think of them.

While you have the manager working on their 12-week improvement plan you need to be self-disciplined and not introduce daily new priorities that will prevent them from delivering on your plan. At this point, they are going to be feeling quite vulnerable and therefore may be reluctant to push back against conflicting priorities coming from you.

Summary

The “management revolving door” is a disaster for your business. Apart from the direct recruitment and severance costs of hiring and firing manager after manager, the revolving door will stall your business’ progress and prevent you from growing successfully. The constant changes in leadership will destroy staff morale and lock in poor culture. The impact on your own morale can also be significant as you try unsuccessfully to take a step back and build a succession plan, only to see your plans thwarted as yet another manager “fails”.

Addressing the revolving door starts with a recognition that the problem is your business’ culture and processes, not the guy at the top. Many of these cultural and process issues have been created by you over many years as you grew the business, so be prepared to listen and be challenged. Some cherished practices may need to go before a permanent change can be achieved.

It is also important to be patient and recognise that the problems that you had before you hired your new manager will not miraculously disappear when they arrive on the scene. Expect your manager to develop a plan and work to it. Give them regular feedback on that plan. Be prepared to ride out the occasional rough patch as long as your manager is delivering on their plan and committed to delivering the fundamental cultural and process change that your business needs.

Watch out for the warning signs on their leadership style, but again give feedback to them as soon as you have concerns and if things get bad, ask them to put together a plan to improve their own performance rather than simply reacting on an ad hoc basis. And remember, the old adage “praise in public, criticise in private” also applies to your managers, so be discrete about performance management and do not discuss your manager’s performance with their subordinates.

Never forget that you and your manager have a common goal – their success and longevity in your business. Your efforts should, therefore, be focused on achieving that goal with them so that they have a long, successful and rewarding career in your business and you can take that step back or shift your focus to the long term future of your business confident in the knowledge that your business is in good hands.

Learn the Seven Reasons Not to Fire Your Factory Manager and the One Reason You Should

Learn More About the TXM Approach to Lean Leadership