I recently re-read (via audio book) “The Goal” by Eliyahu M. Goldratt. Written 35 years ago, this is one of the most influential books about manufacturing ever written.

One of the first “business novels”, “The Goal’ is a highly readable account of how a fictional factory manager turns around the performance of his operation through application of Goldratt’s “Theory of Constraints”.

What Is the Theory of Constraints?

The Theory of Constraints (TOC) is a management philosophy developed by Goldratt and built on a simple principle. That is, that the throughput of any process cannot exceed its slowest step, also known as the bottleneck. In “The Goal”, the plant manager, Alex, at first cannot see the bottleneck. This is because the plant is set up to optimise efficiency at every individual step in the process. Each manager is responsible to manage costs and efficiency for their own department or work centre without regard to the overall process.

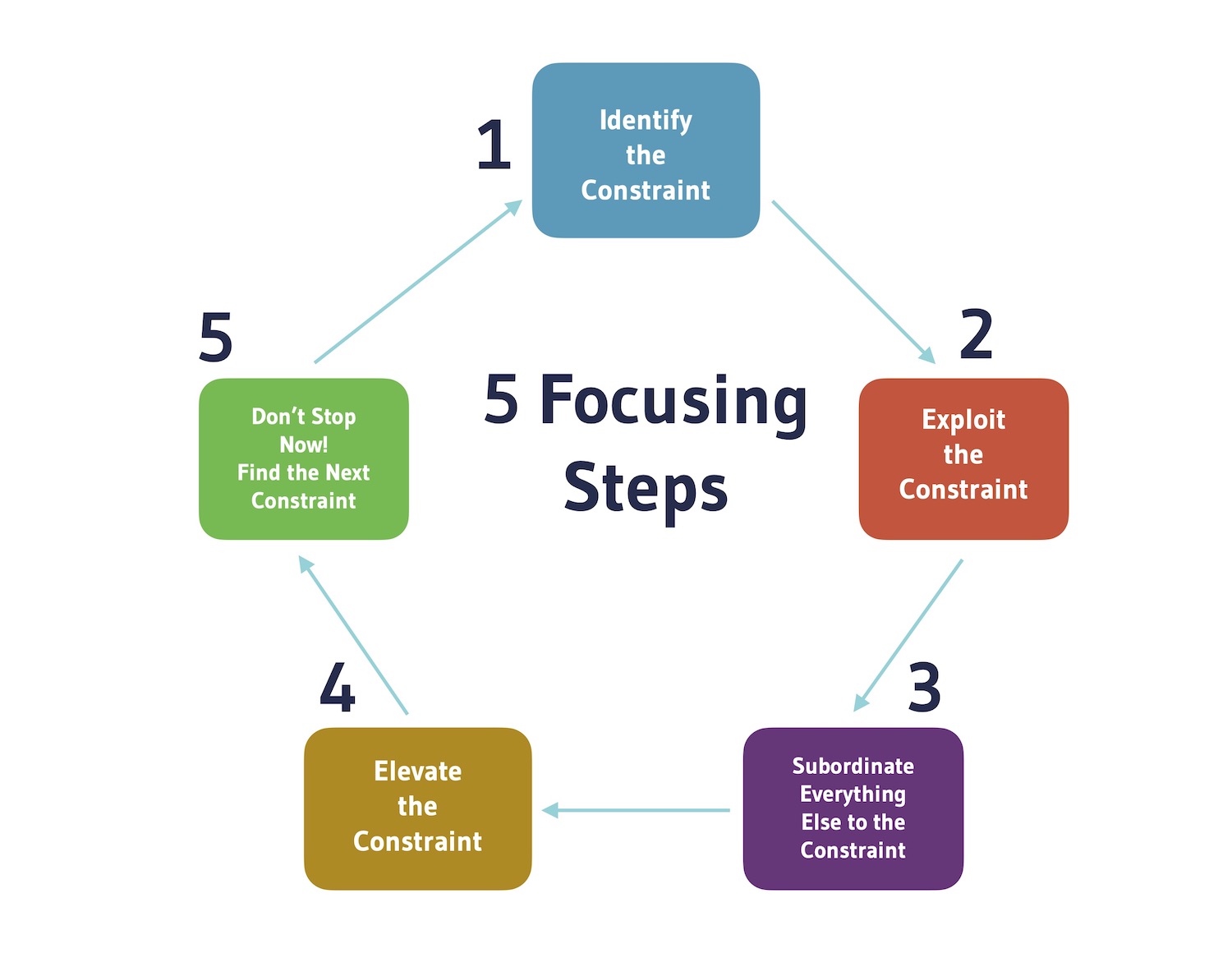

After a chance meeting with a wise Israeli Professor called Jonah, the Plant Manager, Alex is gradually introduced to and applies the Theory of Constraints (TOC). This starts with a recognition that that the “goal” of the business is not to increase efficiencies or reduce costs, but simply to make money. Goldratt highlights just three key measures to control business performance – throughput, operational expense and inventory. To make more money, the business needs to maximise throughput while minimising inventory and operating expense. This is achieved through five focusing steps:

- Identifying the system’s constraints or bottlenecks.

- Deciding how to exploit the constraint – making sure it is 100% utilised

- Subordinating everything else to the above decision – meaning that other steps in the process should be focused on supporting the restraint with enough input and never more.

- Alleviating the system’s constraints – increasing the capacity of the constraint to further increase throughput.

- Preventing inertia from becoming the constraint – Once you have alleviated the constraint, you will find a new constraint in the process. Therefore, to continue increasing throughput you will need to go back to step one and apply the four previous steps to the new constraint.

In the book, Alex the plant manager listens to Jonah, applies the Theory and, after many setbacks, turns around the performance of his plant, gets promoted and saves his marriage!

Does the Theory of Constraints Work?

This is an important question, given that Goldratt was an academic, not a manufacturing leader himself, and that the theory is exactly that, a theory. Personally with over 32 years in manufacturing, I have not come across any businesses who could attribute their success to the Theory of Constraints. There is also very little academic research, beyond Goldratt’s own work supporting the effectiveness of this approach. However, this does not mean that the theory is not useful.

The five focusing steps are a powerful tool and Goldratt’s insistence that businesses focus on three key metrics – throughput, operational expense and inventory helps cut through the confusing maze of measures that many businesses find themselves in.

Theory Of Constraints Examples

Beyond the simple messages of The Goal, Goldratt’s later works provide more insight into his theories and introduce more sophisticated concepts such as the drum-buffer-rope approach, specific solutions for different types of processes and techniques to extend the TOC approach to the supply chain, finance and accounting, project management, sales and marketing etc.

Let’s dig in further:

Manufacturing

In a production line, if the assembly process takes longer than other stages, it becomes the bottleneck.

By ensuring assembly workers always have the necessary parts, the constraint is exploited to maximize throughput.

Project Management

If product launches are frequently delayed, TOC can help identify the biggest blocker and address it using the five focusing steps, which include identifying and exploiting the constraint.

Supply Chain

A shortage of raw materials can delay production. By identifying this as a constraint, a company might seek alternative suppliers or materials to alleviate the delay.

Healthcare

Adding more beds to a hospital won’t improve care quality if the real constraint is a bottleneck in the emergency department.

TOC can help identify and address such constraints to improve patient care.

Sales and Marketing

If sales are limited by market demand, TOC can identify this as a constraint and suggest strategies to increase demand or diversify the market

How Does Theory of Constraints Compare to Lean?

Interestingly Goldratt addresses this very question in a lecture that is attached at the end of the current audiobook of “The Goal”. In fact, there are many similarities, which is not surprising since Goldratt’s work draws on many of the same sources and previous work that informed Toyota in developing the Lean approach.

The most important point of agreement is the need to focus on the throughput of the whole process rather than the performances of individual work stations or process steps. Ultimately our customers buy finished products and so it is our ability to deliver finished products on time and in full that really determines the success of our business, not whether the efficiency of a particular production cell buried in the bowels of our plant has a local efficiency of 80% or 90%.

With TOC this is achieved by identifying the bottleneck and focusing on increasing the throughput of that bottleneck.

The Lean Approach (Lean TOC)

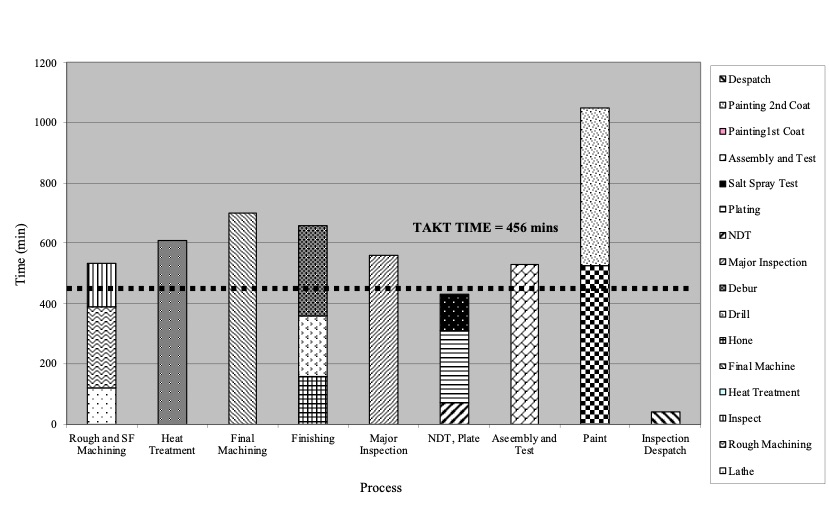

In a Lean approach, which we call Lean TOC, we aim to match the throughput of the process to the rate of customer demand or takt time. The ideal of Lean is level production, where each step in the process works at an even pace that is matched to the takt time. Essentially this allows for bottlenecks to be quickly identified, because when an individual process cannot keep up with takt time, then it becomes a bottleneck. We can see this with a line balance chart such as the one in Figure 2 below.

In this case, even though the customer was requiring one unit every 456 minutes, the process is limited by the constraint of painting to a throughput of one unit every 1050 minutes. A TOC approach would then apply the five focusing steps to this constraint until it was no longer a constraint and then move on to the next constraint, in this case final machining.

Where Lean and TOC differ is that the Lean approach focuses on matching throughput to takt time, while TOC aims to continuously increase throughput to “make more money”. This is a subtle difference, but an important one. In my view Lean is a “customer lead” approach aimed at fulfilling the needs of the customer exactly. If sales increase, then the process needs to be reset to match the new takt time.

However, TOC is a “production lead” approach that aims to continuously increase throughput on the assumption that sales can just sell more. The approach to managing the flow of production in Lean and TOC also has subtle differences.

The Differences Between TOC and Lean

In TOC the approach is called Drum-Buffer-Rope. The drum is the constraint which drives the throughput by setting the “drum beat” throughout the plant. Buffers are placed upstream and downstream of the constraint so that the constraint always has a constant supply of inputs and the downstream processes always have a constant supply of outputs from the constraint. The rope is the way work is released into the process at a standard lead time ahead of the constraint equal to the size of the buffer upstream of the constraint.

In Lean we use a value stream map to visualise the end-to-end process and develop a “future state” to deliver improved performance. Like the drumbeat in TOC, we calculate the “pitch” as interval at which we release work into the process. However, unlike the TOC drumbeat, the pitch is determined by the customer demand (takt time) not by the constraint. Work is released at the pacemaker process, which is not necessarily the constraint process. Downstream of the pacemaker work flows at the level rate in the sequence that matches the pitch.

The pacemaker then “pulls” products from processes upstream. In Figure 1 the takt time is very long at 456 minutes – essentially one unit per day, in this case the pitch and the takt time would be the same. Therefore, once we have balanced the process and ensured that all process steps can meet the takt time, we would release one new job per day at the pacemaker (in this case rough and SF machining) and then each downstream process would be required to also complete one job per day. Where processes have a variable output, or long changeover times then a first-in-first-out lane (FIFO) might be inserted to act as a buffer between processes.

As you will quickly see, these are quite technical considerations and arguably one could achieve a viable outcome with either a TOC or a Lean approach.

The Theory of Constraints’ Big Blind Spot – People

As a management system, the Theory of Constraints has one massive blind spot. As you read “The Goal” you will learn how Jonah convinces Alex and then Alex convinces the team of his plant to implement the Theory of Constraints. This is achieved through the logic of their arguments. Jonah and Alex explain the ideas to the team and the team, with a bit of resistance eventually applies the ideas because they are right and logical. Once the management is convinced the rest of the people in the plant pretty much do as they are told. Unfortunately, this is not a very effective way to achieve change in an organisation. In reality people don’t just “do as they are told”, particularly when what they are being told seems counter-intuitive and is the opposite to the historical culture of the organisation, as it is with TOC (or Lean).

By contrast, Lean is a system of management that is built on a foundation of engaging and respecting people at all levels of an organisation. Lean assumes that everyone in an organisation can help with solving problems and making improvements in contrast to the top-down paternalistic approach assumed in “The Goal” and TOC.

To reinforce this, I visited a factory in the UK that proudly promoted its efforts in applying TOC. I am sure that they had identified and alleviated their restraints and increased their throughput. However, walking the floor of this plant I could see evidence of waste and non-value-added time everywhere including unnecessary, motion, transportation and waiting time. There was also no evidence of front-line staff being engaged in improvement. There were no metrics displayed in the workplace, no sign of staff involved in solving problems, no sign of staff input into the layout and organisation of the workplace (which was very poor). While improvement may have been made at the top level and throughput increased, there was still massive opportunity to make further improvement by engaging people from the bottom up.

Lean Has a Bigger Tool Box

TOC is often described as a management philosophy, but in fact it is a really a set of management tools aimed at solving a particular set of problems in organisations. The tools are based on some wonderful clear thinking and make a lot of sense and probably work well in many cases, but they fall far short of providing an overall road map to run a manufacturing or supply chain organisation.

Even within the implementation of TOC there are large gaps that need Lean solutions. For example in alleviating the constraint, TOC will often suggest reducing downtime, improving reliability and reducing set up times. But it provides no suggestions on how this might be done. Lean by contrast, provides proven techniques such as single minute exchange of die (SMED) to reduce set up times and total productive maintenance to reduce downtime, all within the framework of an overall cohesive management system.

Summary

“The Goal” and the Theory of Constraints have been highly influential on management thinking over the past 40 years. The Theory of Constraints shares many important principles with Lean thinking, with which it shares common roots in the management research of the 1930’s to the 1950’s. However, the Theory of Constraints is a limited set of tools that, on its own is unlikely to deliver sustained transformational change in organisational performance.

The most important gap is the failure to recognise the need to address people and culture in order to achieve sustained change. This is reinforced by the absence of academic research and case studies demonstrating TOC’s track record in isolation from other improvement approaches. Instead, TOC provides a useful theoretical framework to think about an organisation and highlight improvements that will probably take a Lean approach to deliver.

Lean, by contrast is an overall complete management system. Its effectiveness has been reinforced by multiple academic studies showing the superior performance of “Lean” organisations to those with more traditional approaches across a range of industries. Importantly Lean recognises the centrality of people and culture to organisational performance and provides a framework to engage people at all levels and improve culture. Lean also provides a broad range of management tools to improve all aspects of an organisation.

TOC is a useful approach and The Goal is an entertaining and thought provoking book that I highly recommend. However, application of the Theory of Constraints should be seen as a useful set of tools to solve particular problems in planning and the supply chain, not a pathway to operational excellence. We would recommend that TOC be applied within a Lean management system rather than as an alternative to the more comprehensive and proven Lean approach.

At TXM our Operational Excellence consultants are experts in Lean thinking as well as a range of other management approaches including the Theory of Constraints, Agile, Supply Chain Management and Industry 4.0.