Article by Tim McLean – Managing Director

The last 30 years have witnessed one of the greatest economic achievements the world has ever seen. The rise of China from an impoverished, largely agrarian economy to become one of the world’s second-largest economy and a global manufacturing super-power. There have been huge benefits of this transformation. Over 500 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty while western economies have benefited from low inflation, driven largely by the flow of low-cost products from China. I visited China over 30 times between 2004 and 2016 and saw the transformation in well over one hundred Chinese factories firsthand.

China Sourcing in 2008

In 2008 I was given the job of outsourcing a large number of complex sheet metal components for the Australian arm of a major US high technology manufacturer. At that time, it seemed like the question western manufacturers faced was not, if they would relocate their facilities to China, but when. Hiring a semi-skilled factory worker, such as a welder, costs less than ¥1000 per month (around $US125) compared to at least 20 times that for the equivalent worker in the west. As well as costs for land, energy and regulatory compliance were cheap compared to the west. The ex-works price for the components I helped outsource was between 40% and 75% less than the previous cost of in-house manufacture in Australia.

However, even then, the writing was on the wall. That year I did some modelling on the long-run competitiveness of China and results startled me. When modelling the benefits of outsourcing projects, purchasing teams tended to calculate costs based on “today’s dollars”. The problem with this was that inflation in China was running at double the typical level in the west and wages were probably rising five times as fast.

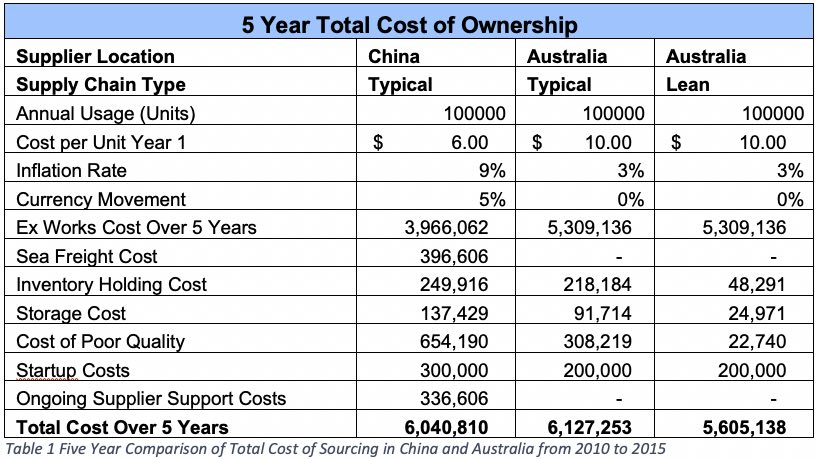

On top of that, the Chinese currency would inevitably rise over time (as it has done). Finally, the models on which outsourcing was based usually failed to account for the hidden costs of outsourcing such as inventory holding costs, warehousing, supporting China suppliers (in China) and quality risks. As the table below shows, factoring in these “hidden costs” along with inflation, and relative inflation and currency, the total cost of the China-sourced product would overtake its local western equivalent within five years. This was despite the Chinese product being 40% cheaper ex-works.

This model assumed that the quality of the Chinese product was the same as that of the local alternative, but the consequences of a quality problem are much greater with a longer supply chain. What this analysis also showed was how many suppliers in western markets squandered their competitive advantage by demanding long lead times that could be matched by imported projects. By establishing Lean production systems, the local supplier could offer smaller lot sizes and shorter lead times than the imported alternative, creating a large competitive advantage.

How has the Prediction Faired?

Over the past 10 years since 2010 costs have grown as the model predicted. That Chinese welder now earns around ¥5000 per month and the currency rise means that it corresponds to more than $US700 or six times more than 2010. As well, the cost of industrial land on the east coast of China is often twice the cost of equivalent land in the US or Europe and energy costs have risen dramatically as well. Wages and land are cheaper in inland China, but China’s inefficient logistics infrastructure means the cost of getting the goods to the coast often outweighs any savings.

On top of this, the Chinese worker is on average, 50% less productive than their western equivalent[1]. When total costs are considered the competitive advantage for many products have disappeared. This is particularly the case for bulky products with relatively low value-added. For example, structural steel, plastics moldings, and sheet metal enclosures are now often more expensive sourced from China.

[1] Ref: Ian Colotla, Yvonne Zhou, Victor Du, John Wong, Jeff Walters, Justin Rose, and Lars Maecker, “China’s Next Leap in Manufacturing”, Boston Consulting Group, 13 December 2018

It’s Not Just About Cost and It is Not Just China

In a time of high geopolitical instability, extended supply chains where inputs are sourced all around the world are looking particularly risky. Companies are increasingly bringing their supply chains closer to final production and their customers in order to reduce their exposure to interruptions to the flow of trade as well as political instability in source countries. Business is becoming more dynamic and competitive. In everything from fashion to consumer electronics product lifecycles are shortening and markets are fragmenting. While in the B2B space, customers are increasingly demanding bespoke solutions. Meeting these fast-changing needs is near impossible if your supplier lead times are measured in months.

In a world of the 24-hour news cycle and “viral” social media stories, corporate reputations can be destroyed in a few hours. Businesses need to know where their products come from, what they contain and who has been involved in their production. Issues like modern slavery, human rights abuses, environmental abuses, bribery, and product substitution are well documented in almost every low-cost country, including China. An increasing number of companies have found their brands damaged in the public arena by the actions of suppliers that they were unaware of and probably had little or no control over. However, those fine details do not concern the Netizens. It’s your brand that they recognize and will attack.

Finally, the risks are also financial. The biggest driver of inventory in your supply chain is lead time. From our experience with small and medium-sized manufacturing and distribution companies (SMEs), supply lead times of 12-20 weeks or even longer are not uncommon when sourcing from China and other low-cost countries. As well the suppliers often demand large minimum order sizes. The result is very high levels of stock with stock-turns sometimes less than three times per year. This places a heavy demand on cash flow and also represents another level of risk, multiplying the impact when products become obsolete or when quality issues are discovered.

The Danger of “Doubling Down”

One response I have seen to the changing economics of low-cost sourcing is what I call “doubling down” by looking for even cheaper suppliers in less developed parts of China or in “new” developing countries such as Bangladesh. Ultimately this strategy only fixes one problem, rising unit costs, and generally makes all the other problems worse. The new, “cheaper” suppliers inevitably have less sophisticated quality systems, opaque regulation and governance, longer lead times, poorer financial stability and less reliable supply chains. Price may go down, but risks and inventory will go up and supply chains become even more inflexible. I have even seen companies pursuing the doubling down strategy to the point of setting up “rework departments” in their factories dedicated to the reworking of poor-quality components from “low cost” countries. How this approach can ever be justified escapes me.

I recently showed an audience at a workshop in the UK the photo below of an anonymous Chinese factory. This factory was a key supplier to a major global hardware products distributor. The question I first asked is “who has seen a Chinese factory like this”. The answer (given with a wry smile) is that most had. I then asked the question “If this supplier was in the UK, would you buy from them?”. The sense of embarrassment in the room was palpable. However, if we would never buy from a supplier like that in our own country, why would we even dream of buying from them in China or elsewhere? But sadly, these are the type of factories many western buyers are “doubling down” to.

The Move is On

The word “re-shoring” first appeared around five years ago referring to the trend for mainly US companies to bring production back home to the USA. This trend has now become a tidal wave in recent years. In Europe and North America, we see the wholesale relocation of production back closer to home. A recent six-page feature in The Economist[2] confirmed the trends we are seeing in the factories we visit around the world.

[2] Ref: “Supply chains are undergoing a dramatic transformation” The Economist Special Report, 11 July 2019.

Importantly many companies are bringing production in-house rather than shifting from Chinese or other Asian sources to local suppliers. We are finding companies both large and small increasing their level of vertical integration. By gaining control of more of their supply chains these companies are increasing their share of the value-added in their products.

More importantly, by shortening their lead times, they are better equipped to respond quickly to changes in their market by introducing new products or ramping up or down production to meet demand. Technology is also facilitating this move to vertical integration. Once a machine tool required a highly-skilled tradesperson to operate it. Now such technology has a high level of inbuilt intelligence and can be managed successfully by semi-skilled staff.

Making the Most of Your Shorter Supply Chain

Having a local, vertically integrated supply chain does give you control and eliminate some of the risks of extended international supply chains. Sadly, we see manufacturers who have made this transition who still have order lead times measured in months as well as mountains of inventory. Therefore, redesigning your supply chain is not as simple as just purchasing some machinery and hiring people. Take the time to develop a value stream map of your end to end supply chain from your suppliers to your final customer.

Consider both product and information flows. Calculate total costs through the supply chain such as those considered in Table 1 above. Applying Lean thinking will help you design a supply chain with considerably shorter lead times. This has many benefits, reducing inventory, reducing the risk of obsolescence and providing you the opportunity to respond faster to your market with a greater range of products more customized to your client’s needs.

Will China Sourcing Disappear?

In a word, no. China’s competitive advantages are built on more than cheap labor. China’s development has more in common with Japan than developing countries in South and Southeast Asia. It has been accompanied with a huge investment in high-quality infrastructure and an excellent education system. China has become the dominant manufacturer in a number of key sectors including electronics, toys and consumer goods.

This has led to massive economies of scale as well as efficient “clusters” where all the key suppliers to an industry are clustered in a tight geographical area. This gives companies in these areas a huge advantage in access to inputs, people with relevant skills and know-how. It will be hard for any other country to replicate this at the scale that exists in China.

As well, China has a massive economy and is the largest global market for many products. For example, China consumes more elevators than the rest of the world combined and is the largest global car market. Therefore, it makes sense if you are in these markets that you have a significant presence in China.

However, the days of simply outsourcing your product or your key inputs to a Chinese or Asian supplier to save a dollar are coming to an end. Wise businesses will be already planning for a more localized supply chain.