One of the key pillars of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), the “Lean” approach to maintenance is Autonomous Maintenance. This is often referred to as “operator maintenance” where operators get involved in maintaining machinery rather than leaving it all to the maintenance crew.

As a former plant manager, “operator maintenance” is a very attractive concept as operators are always on the job, get to understand the equipment intimately and generally cost less to employ than maintenance technicians.

However, talk to operators in most manufacturing environments about doing their own maintenance and you will not get a positive response. Operators usually feel that they have enough to do without doing the job of the maintenance crew as well. In many workplaces the mere suggestion of “operator maintenance” will invite a discussion with the local union delegate and claims for more wages.

The Reality Of Operator Maintenance

In reality, in many factories “operator maintenance” happens all the time and the evidence is not hard to find. Slightly ajar electrical or PLC boxes where operators have obtained access to reset equipment when it trips out, dented powder hoppers where operators have needed to do some “panel beating” to get the product to flow or strategically placed pieces of cardboard or sticky tape on conveyors to prevent product jams.

In fact, operators are usually highly motivated to keep production going and will often take it into their own hands to overcome the problems that cause stoppages.

The problem with this approach is that usually the operator maintenance is covering up real problems in the equipment, this informal maintenance will usually make things worse and often exposes the operators to serious safety hazards (especially where access to live electrical cabinets or moving equipment is involved).

So, it is important to realise that autonomous maintenance is not just “operator maintenance”.

How does Operator Maintenance fit within TPM?

To understand operator maintenance (or autonomous maintenance and continuous improvement), it needs to be put in the context of an overall TPM program.

The essence of TPM is a collaborative approach to maintaining equipment where operational and maintenance staff work together to maximise machine performance. Machine performance is usually measured as overall equipment effectiveness (OEE).

The 8 Pillars of TPM

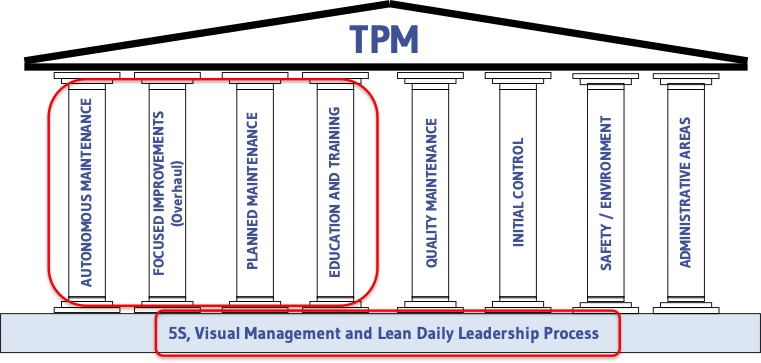

TPM is usually described as being made up of eight pillars of which autonomous maintenance is one. For TPM to be successful the pillars need to work together to drive improvement in OEE. The eight pillars are:

- Focused Improvement – Where small groups of employees work together proactively to achieve regular, incremental improvements in equipment operation.

- Autonomous Maintenance – more about that later.

- Planned maintenance – which brings together preventative and predictive maintenance strategies.

- Training and education – where operators and maintainers gain the skills to maintain equipment effectively.

- Early equipment management – where improves new equipment designs, maintenance becomes simpler and more robust due to practical review and employee involvement prior to installation.

- Quality Maintenance – where the quality of maintenance work is measured and improved.

- Administrative TPM – which extends TPM benefits beyond the plant floor by addressing waste in administrative functions.

- Health, Safety and Environment – Which eliminates potential health and safety risks, resulting in a safer workplace.

At TXM we would probably add problem solving and root cause analysis, where data is collected on machine performance, analysed and the root causes of the most common failures are identified and addressed.

The Unique Role of Operators

Operators are the people who spend the most time with machines. Often, they can work with a single machine for years and become highly tuned to its problems. They also regularly interact directly with machines when they set up the machine for a new product or adjust the process during production runs.

Unfortunately, management and maintenance teams are usually not very good at listening to operators when they report what they observe and, as a result, operators will often give up on reporting issues. The machine will then get into a pattern of repeated failures of a similar nature, leading to frustration all around.

Maintainers will often blame operators for “breaking the machine”, and operators will blame maintainers for “not fixing it properly”. Naturally, all this blame is unproductive, and what is really needed is for operators and maintainers to get together and discuss what they have both observed about the machine.

Initial cleaning and inspection – the First Step to TPM

The initial cleaning and inspection step of TPM can be a good way to break this cycle. With the machine stopped, maintainers and operators work together to go over every aspect of the machine and identify everything that is not to standards.

Whether it is a major oil leak or a badly scratched inspection panel, every issue is tagged (Yellow tag), recorded, and a plan (or work order) is made to address it. Usually, machines will also be given a thorough clean (initial cleaning), and often repainted to emphasise the change.

The Role of 5S

Once the machine has been upgraded and cleaned then the challenge is to keep it that way. This is where 5S becomes important, particularly the “shine” step within 5S. Cleaning is in fact the first step in autonomous maintenance. Once a machine is clean, it is much easier to see problems such as oil or air leaks, damaged parts or missing fasteners.

General inspection

Once the machine is clean, the next step in autonomous maintenance is general inspection. This merely means that the operator needs to observe and report abnormal conditions. Very few operators will feel comfortable when their machine is making a strange noise or not running smoothly.

However, some may not report these things if they do not think it is their place to do so or feel that they will be ignored or, worse, mocked. Instead, operators need to be provided with some regular checks to carry out on their equipment and educated on what to look for and listen for.

Checklists and one-point lessons are invaluable in helping operators have the confidence to know what to inspect and how.

Aligning

Operators are usually the ones to complete changeovers on production lines. This work usually involves tasks such as adjusting machine heights, aligning product guides or adjusting speeds. Every machine will have its optimum settings for every job it runs. However, too often we just leave it to operators to figure out these settings at every setup.

As a result, no two setups are ever quite the same and deliver the same result. If a setup is not quite run, making adjustments while the machine is running can be difficult and dangerous, while stopping the machine entirely can be costly and lead to product loss.

Therefore, setting standards for the alignment of machines that operators can follow every time can lead to faster setups and smoother running. It can also prevent product jams and other issues that can do serious damage to machines.

In my view, getting operators to clean, inspect and properly align the equipment they are running and report any issues that they find will deliver a significant improvement in performance. However, all of these skills are tasks that already form part of an operator’s role and no special maintenance skills or equipment are required.

Retightening

Where things come loose during a run, such as a conveyor guide or a machine cover, often operators can tighten these without needing to use a special tool if hand wheels are provided. Again, retightening a loose part at a critical time can prevent a catastrophic failure.

Where specialised tools are required, these should be simple and operators must be given training to perform the retightening task.

Importantly operators need to know when the need to tighten a belt or a chain drive is a symptom of a larger problem (e.g. the chain or belt is wearing out) and then report the issue rather than continuing to tighten the part until it fails catastrophically. Simple one-point lessons and guides showing acceptable and unacceptable levels of wear can help here.

Picking up tools to tighten equipment can become a culture change challenge if operators are not used to using these tools.

However, if operators have already been engaged in machine care through the focused improvement, clean, inspect and align steps then they are likely to be more engaged and more willing to take on the retightening step.

Lubrication

The same applies to lubrication. If operators are to take on the role of topping up lubricants or other liquids or pumping grease into bearings and joints then they need to clearly know what lubricants to use where, when and in what quantities so they do not over-lubricate or use the wrong products.

Colour coding is very useful here for lubricant types, simple tools such as dipsticks.

In Conclusion: Not So Scary After All

Cleaning, inspection, aligning, retightening and lubrication is usually all operators will ever need to do in autonomous maintenance. More invasive and complex maintenance tasks should be performed by appropriately skilled maintenance tradespeople.

For operators, the key change is that they take on a role in caring for equipment as well as running it.

Often (particularly with the first three steps) autonomous maintenance does not require operators to learn many more skills than they already have. Importantly though, it focuses on those skills and also provides operators with the knowledge of what to look for and how to perform those key tasks correctly.

As for the informal “operator maintenance” quick fixes these need to be eliminated. As trust builds between machine operators and maintainers, they will realise that a better approach is to report the issue, knowing it will be taken seriously, and work together to find and eliminate the root cause. They are also a lot less likely to do lasting damage to the machine or themselves.

Autonomous maintenance is a powerful and effective tool for improving machine performance, but to work it needs to be implemented as part of an overall TPM program, rather than an isolated initiative and please don’t refer to it as “operator maintenance”.